As Easter weekend begins and this time of being housebound continues, I find myself thinking beyond the confines of my home. I find myself thinking wistfully of some of the places around the world I’ve had the privilege to visit, and some of the Easter-related objects I’ve found there. Here are a couple of objects I discovered in my round-the-world Epic journey that help tell the story of Easter.

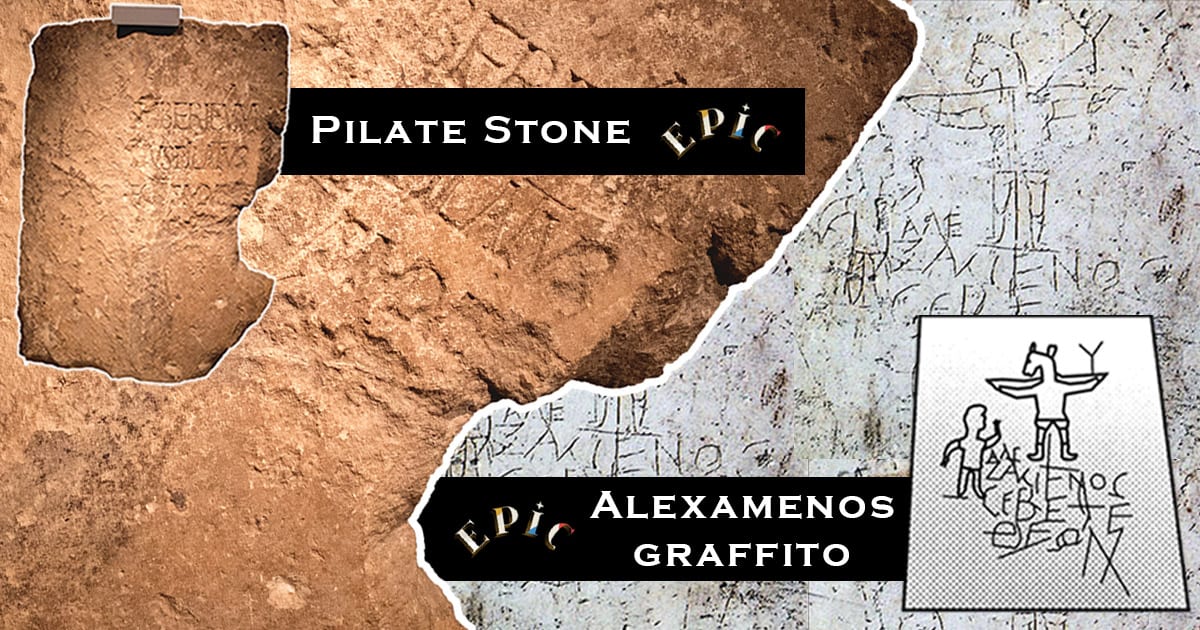

Pilate Stone

Any study of Christian history will show that time and again skeptics have insisted that certain elements of the Bible cannot be true because they have not been corroborated by the historical record. This was exactly the case with the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, who plays a particularly important and tragic role on Good Friday. For many years skeptics insisted that he was a fabrication of the early Christians, and they backed their claim by showing that no one had found archaeological evidence of his existence. “If he really existed, why haven’t we found any original references to him?” This all changed in 1961 when an Italian archaeologist was excavating ancient Caesarea and found a limestone block that formed part of a staircase. He soon saw that this block had been recycled from an earlier building that had been torn down, for on the back of it was an inscription. Although some characters were missing, it was not difficult to reconstruct the wording:

[in honor of] Tiberius

[Pon]tius Pilate

[Praef]ect of Judea

The stone had once dedicated the building, probably a temple, to Tiberius Caesar. This was the first, and to that point the only, object that bore Pilate’s name, but it was enough. Now no one could legitimately doubt that Pilate had indeed existed and that he had indeed governed Judea. The Bible had once again been vindicated. The so-called “Pilate Stone” is now on display at the Israel Museum, alongside a crucifixion nail of the kind used to crucify Jesus. And in its own way, this little broken piece of stone affirms what Christians already know—that where the Bible communicates history, it does so truly and infallibly.

Alexamenos Graffito

From Jerusalem we head to Rome, and to the Palatine Hill, once the very center of Roman culture and seat of Roman power. In the Palatine Antiquarium Museum is a little piece of ancient graffiti that is surprisingly important to the story of Easter. This particular piece had been carved into plaster and was discovered in 1857 during archaeological excavations. It was soon dubbed the Alexamenos graffito. It appears old and rather faded, and the original design is difficult to discern, yet a close look or a careful tracing reveals two figures and a string of Greek characters. To the left is a man raising his hand in adoration, a posture of worship or prayer. To his side, rising above him, is a second man suspended from a cross. Crucifixions were common in Rome, and this second man looks as you might expect—arms outstretched, pinned to a crossbar. His feet are planted on a platform, and he is wearing some kind of garment that is covering his lower body. But what distinguishes this man from other crucified criminals is that while he has the body of a man, he has the head of a donkey. The inscription near the drawing sarcastically explains the scene: “Alexamenos sebetai theon,” “Alexamenos worships his God.”

Historians date this graffiti to approximately AD 200, which makes it the earliest surviving depiction of Jesus hanging on a cross. This fact alone gives it great significance. Yet it is also important to note that this is not a religious icon meant to elicit awe or worship. The graffiti is a mockery of an ancient Christian and the God he worshiped. It is a mockery of any so-called God who would die the shameful death of a criminal and any person who would be naive and foolish enough to worship him.

While we don’t know much about Alexamenos, we know that he was a Christian, a man who proclaimed that Jesus is Lord. He worshiped a God who became a man, who lived out his life within the confines of the Roman Empire, and who endured the most painful and shameful death devised by the cruelest minds of that time. Yet Alexamenos did not worship a dead man, but a resurrected, living one. And along with countless other Christians before and after him, Alexamenos was mocked for what he believed.

Approximately 150 years before Alexamenos, the apostle Paul had written that “the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18). Every Christian knows the shame of believing in this truth about God. It’s something so unusual, so unexpected, so unfathomable, and so seemingly foolish. Yet it is something that is fundamental to our faith, for as Paul says in that same letter, “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain. … if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. (1:14, 17). While on Good Friday we remember the shocking, horrifying death of the Son of God, on Easter we remember that he did not remain on that cross and did not remain in the grave. He has risen! He has risen indeed…