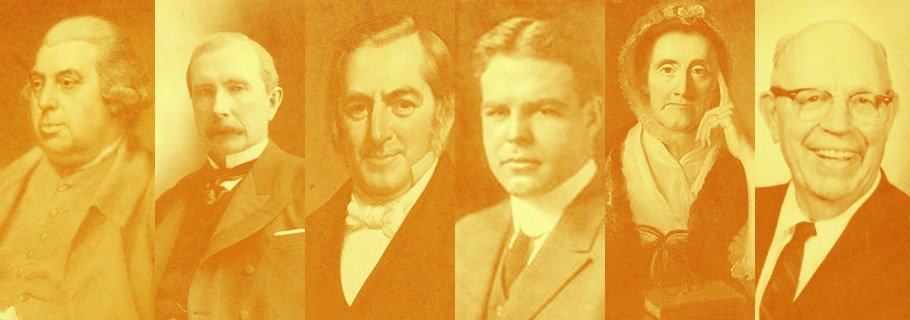

Today I am beginning a series of short biographies of great Christian philanthropists–men and women who used their God-given wealth and privilege to advance his work. We begin with a woman who was the “Queen of Methodism,” an influential leader in the 18th century revival movement, and a great philanthropist.

Today I am beginning a series of short biographies of great Christian philanthropists–men and women who used their God-given wealth and privilege to advance his work. We begin with a woman who was the “Queen of Methodism,” an influential leader in the 18th century revival movement, and a great philanthropist.

Selina Hastings was born on August 24, 1707, the daughter of Lord Washington Shirley and Lady Mary Shirley. A child of privilege, she spent her childhood in Leicestershire and her family’s Irish estates. In 1728 she married Theophilus Hastings, the ninth Earl of Huntingdon, and this marriage gave her the title Countess of Huntingdon.

In his biography of George Whitefield, Arnold Dallimore notes “the remarkable Christian witness that [Lady Huntingdon] maintained among Britain’s nobility.” In fact, as one of her own biographers tells us, “Lord and Lady Huntingdon constantly attended wherever [Whitefield] preached.” As a result, she grew to be a devout Christian, passionate about inviting others of British nobility to hear this remarkable preacher and the gospel he preached. Or, as another Whitefield biographer, Luke Tyerman, wrote, “Wherever she went she took her religion with her, for her religion was a part of herself.”

Her Conversion

How did Lady Huntingdon come to trust in Christ? Here’s a lengthier excerpt from Dallimore’s biography:

Since her earliest days Lady Huntingdon had lived an exemplary life, remaining aloof from the coarse pleasures of high society and conducting herself in a highly virtuous and religious manner. In turn she rested in the assurance that her personal righteousness was sufficient for the saving of her soul.

But this assurance was shaken under the hearing of the Gospel. This was first as she listened to the twenty-two-year-old Whitefield in 1737 and then in 1739 when her sister-in-law, Lady Margaret Hastings, who had been converted under the ministry of Benjamin Ingham, testified to an experience of “the new birth” and to a peace and certainty that “the Christianity of creed and ritual” could not provide.

But it was as she lay on a sick-bed and seemed near to death that she especially felt the worthlessness of her self-trust.

Helen Knight continues the narrative:

Then … from her bed she lifted up her heart to God for pardon and mercy through the blood of his Son. With streaming eyes she cast herself on her Saviour: “Lord, I believe, help thou mine unbelief!” Immediately the scales fell from her eyes; doubt and distress vanished; joy and peace filled her bosom, and with appropriating faith she cried, “My Lord and my God!”

Her Contributions

After her conversion, Lady Huntingdon founded dozens of chapels and funded many of them. Using her right as a peeress, she appointed evangelical clergymen to each. She also supported missionary work in America, and even contributed to the first Methodist theological college, Trevecca College (later Cheshunt College, now part of Westminster College in Cambridge). After embracing Whitefield’s Calvinism (instead of John Wesley’s Arminianism), she founded “The Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion” in 1783, a society of English preachers and churches that continues to this day.

In fact, Whitefield acted as one of Lady Huntingdon’s chaplains and, because she built chapels for some of his followers, they too joined her Connexion. Here, a form of Calvinistic Methodism similar to Whitefield’s was taught. As Tyerman writes, “The services had been attended by considerable numbers of the aristocracy, who would have declined to enter an ordinary Methodist meeting-house.”

Why did she give so much? After her husband died in 1746, she decided to live her life, as Dallimore says, “labouring in prayer, exercising her personal witness and using her wealth and influence to the fullest extent possible in the furtherance of the Gospel.” Or, in her own words, “None know how to prize the Saviour, but such as are zealous in pious works for others.” As Paul says in Romans 1:14–15, “I am under obligation both to Greeks and to barbarians, both to the wise and to the foolish. So I am eager to preach the gospel to you also who are in Rome.” Likewise, the love of Christ constrained Lady Huntingdon to worship God and give to others so that more might trust in Him.

She died on June 17, 1791, and left behind a wish that no one would write a biography of her. It would be 90 years before someone finally wrote an account of her life. In death, as in life, she had no desire to be recognized, so God might receive all the glory.