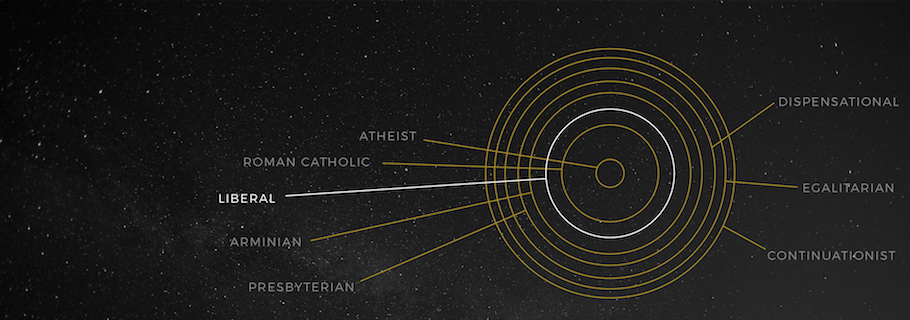

I am now well into a series titled “Why I Am Not…” In an age when so many consider religious beliefs as subjective and irrational, I am convinced that any conviction worth holding must stand up to scrutiny. So how did I come by my faith? Why am I confident in my most deeply held beliefs? These are the questions I’m attempting to answer and I am doing it by looking at some of the beliefs I have weighed but found wanting. I have already told why I am not atheist and why I am not Roman Catholic. Today I want to tell why I am not liberal.

I need to define what I mean by the term. Liberalism arose as professed Christians struggled to reconcile modern minds with ancient beliefs. They found apparent conflicts between science and Scripture, for example, and grappled with how to reconcile the two. Christians had traditionally professed that the inerrant and infallible Word of God is the “norming norm,” the standard that stands above all others. Liberals, though, began to place far greater emphasis on the human mind and were willing to overrule long-held interpretations of Scripture in order to make peace with modern discoveries and sensibilities. At heart, then, liberalism was a matter of authority—the authority of the Bible against the authority of the human mind. One would have to take precedence over the other.

While the terminology of theological liberalism has faded, the spirit of liberalism lives on. To give one ready example, the emerging church movement was little more than modern liberalism masquerading in postmodern clothing. And it is in this context that I first encountered it. Like so many others, I found myself investigating Reformed theology at the very time that the emerging church was in its ascendency. Each of these competing movements had its own attraction, yet they were incompatible because of their opposing views of Scripture.

I believe that the Reformed and Emerging movements each gained prominence as an alternative to the church growth movement. Church growth had dominated the evangelical landscape for many years but many people had become disillusioned with its brand of big-box Christianity, with so much emphasis on form and style but so little on content and orthodoxy. Both movements offered a compelling alternative. The Reformed movement offered historic Protestant theology carried through expositional preaching while the Emerging movement offered relational authenticity carried through community and advocacy. Both were attractive to people weary of yet another program, yet another “next big thing.”

The church I attended at the time was once described by a sarcastic visitor as “just another Saddleback/Willow Creek knockoff,” though that meant nothing to me at the time. As the years went by, the church began to make use of Rob Bell’s Nooma videos which had begun as clever theological inquiry but which soon tiptoed awfully close to liberalism. Some of the church leaders began to read and distribute books by Brian McLaren and other Emergent writers. At the same time, I learned that a close friend was dabbling in older forms of liberalism, first reading books he had borrowed from the local public library and then eventually full-out revoking the faith.

Between the church and my friend I had reasons to investigate liberalism in both its classic and contemporary forms. I did so by reading books. I read James White, James Montgomery Boice, R.C. Sproul, John MacArthur, Michel Horton, Wayne Grudem, and others as well. Few if any of these books dealt with liberalism head-on, but they didn’t need to. These authors presented a united front when it came to a theology of the Bible, and between them they renewed and reinforced my understanding of Scripture’s inerrancy, infallibility, clarity, necessity, sufficiency, and authority. I grew in my conviction that the Bible is inerrant, that, as Grudem says, “Scripture in the original manuscripts does not affirm anything that is contrary to fact.” Or, even better, as the Bible says, “Every word of God proves true” (Proverbs 30:5) and “The words of the Lord are pure words, like silver refined in a furnace on the ground, purified seven times” (Psalm 12:6).

Following behind the doctrine of inerrancy were the doctrine of sufficiency (that God has said through Scripture all that he needs to say in order for us to honor and obey him), the doctrine of clarity (that the central message of the Bible and the appropriate response to it are made clear in its pages), and the doctrine of necessity (that we are utterly dependent upon God’s revelation of himself). And from there it was but a short step to the sweet doctrine of the Bible’s authority (that “to disbelieve or disobey any word of Scripture is to disbelieve or disobey God”). I saw that God was calling me to willingly, freely, joyfully, and immediately acknowledge and obey him by acknowledging and obeying his Word.

To take the Bible at any terms but its own is to reject the Bible altogether.

When I turned my eye back to the emerging church or back to my friend’s classic liberalism, I saw that at the center of it all stood a denial of the authority of the Word of God. These people read the Bible and preached the Bible and wrote about the Bible and professed to honor the Bible, but all the while they denied the full authority of the Bible. They accepted God’s Word on their own terms. But God gives us no such option. To take the Bible at any terms but its own is to reject the Bible altogether.

I am not liberal and never will be. Instead, I am evangelical, joyfully affirming the authority of the Bible while attempting to live according to it. My investigations into liberalism led me out of the church I was part of and into a church that was both evangelical and Reformed. And that serves as an appropriate segue into my next article in which I will discuss why I am not Arminian.